One of my favourite lines in literature is the famous first sentence of The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus. He writes, “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide.” This question forms the core of Babylon, and the anime delves into the topic with great depth and clarity.

At least, that’s what I wish I could have said about this show.

Babylon was an immediate must-see for me when it was announced because it seemed to me like one of those shows that would lead one to question the very foundations of human morality. The name really should have clued me in; Babylon in itself is a Biblical reference to the city of sin, standing in opposition to the new Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation. The attempt towards depth but failure to truly grasp it was disappointing, to say the least.

The audience is presented first with the steadfast and incorruptible Seizaki Zen, a special prosecutor so just that his very name implies justice. The series is mainly set in a fictional extension of Tokyo called Shiniki (literally, “New District”), which is established for the purpose of progressing humankind by pursuing experimental research in science as well as in policy. The machinations of the political elite in itself is extremely shady, and the vote is rigged through the combined desire of all the candidates who really belong to the same political faction that established Shiniki in the first place.

Right off the bat, the show’s main problem is revealed, even though it’s not clear at the very beginning that the show would be problematic as a result. The problem is personified in a single character: Magase Ai, the Whore of Babylon.

The Whore of Babylon is a character that appears in the Book of Revelation, the final book of the Bible that modern evangelical Christians believe predicts the so-called “End Times”, but which many Biblical scholars today believe was a contemporary political critique either of the 7 Churches of Asia or the Roman Empire. Because the Whore of Babylon and her place in Revelation plays such a huge role in the way she is characterized in the show, I believe that it is necessary to examine the Book of Revelation, and the specific role of the Whore of Babylon in it.

The crux of Babylon’s references to Revelation may be found within Revelation 17, which you can find here if you wish to reference it (KJV or NIV). We can identify rather easily a few metaphors used within the show: obviously, Magase Ai is meant to embody the Whore of Babylon, that seductress enticing mankind into sin. Indeed, she also takes the place of Satan in a graphic showing the corruption of mankind from the Garden of Eden.

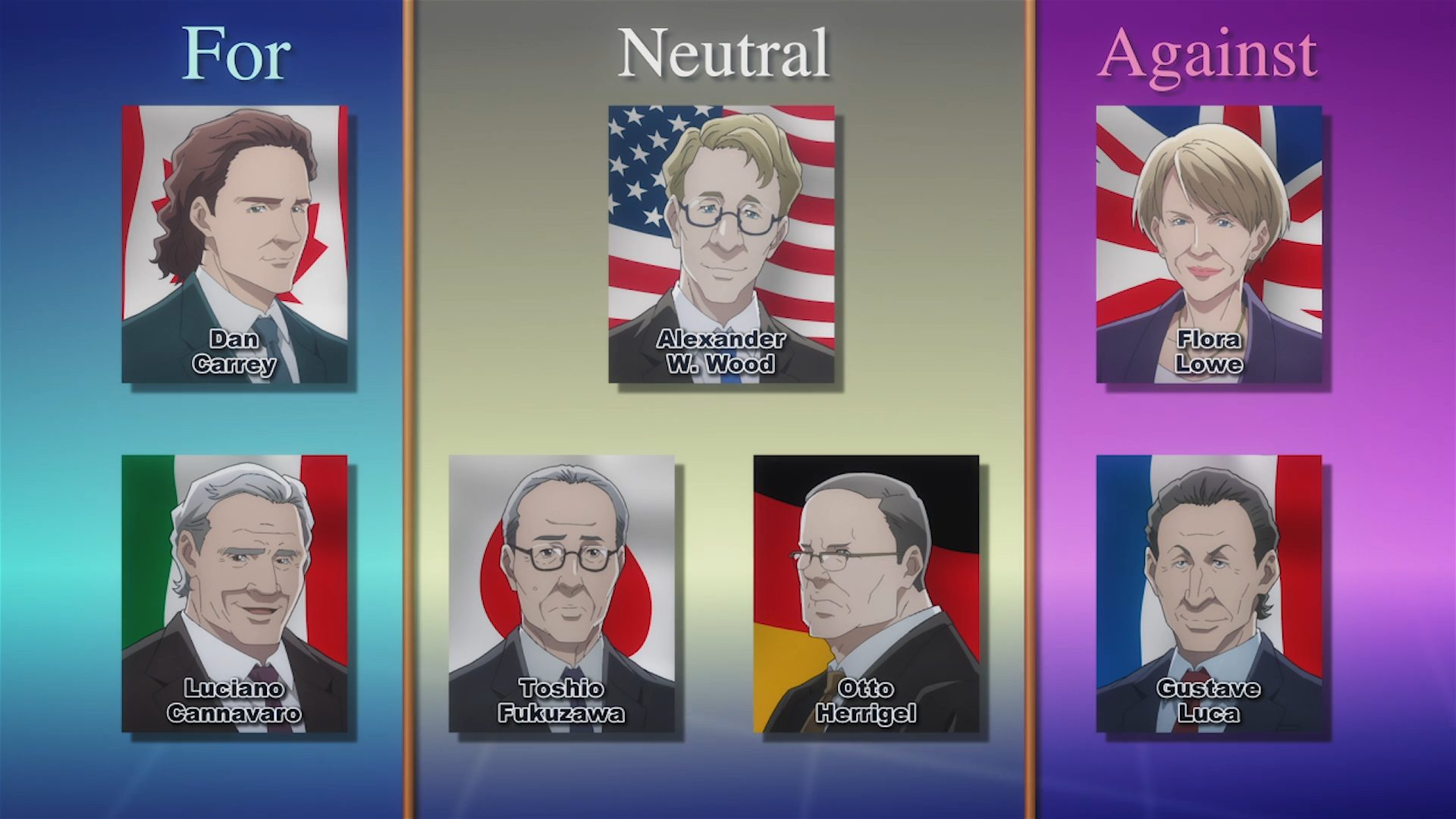

One of the most difficult references to capture would be that of the Seven Kings on whom the Whore sits. The most natural conclusion would be to compare the kings to the G7 that is held in the final two episodes of the show. In this case, then, the five kings who are “fallen” are kings who have given in to their moral preconceptions of the suicide law. The one king who “is”, is the king who is still considering the morality of the suicide law – Alex Wood. The final king who is “not yet come” would then refer to the Japanese prime minister, who is reluctant to begin consideration of and to take a stance on the suicide law. This would then lend credence to the eighth King being Itsuki Kaika. He is the one who pushes the suicide law, and therefore is representative of it, which is how we can view him as “the beast that was, and is not”.

Suicide itself has a tricky history with the Bible. There is technically no proclamation in the Bible that one should avoid killing themselves; indeed, most Christians and theologians would accept it as a natural conclusion from the commandment not to kill one’s neighbor. If one looks to the Bible and history in general, however, suicide was a fairly common and accepted occurrence during the time period which the Bible covers. There are two main positive conceptions of suicide that may be found in the Bible: the idea of suicide as a noble death, and the idea of suicide as an act of repentance. These two ideas are usually found to be enmeshed, with a noble death usually being sought after a Biblical character has found himself forsaken by God. A notable example is the suicide of Judas Iscariot; the betrayer of Christ. That being the case, the suicide law would fit into Revelation 17:8, which states, “The beast that thou sawest was, and is not; and shall ascend out of the bottomless pit, and go into perdition: and they that dwell on the earth shall wonder, whose names were not written in the book of life from the foundation of the world, when they behold the beast that was, and is not, and yet is.”

Magase Ai, being the Whore of Babylon, sits astride the beast that is the suicide law. She is “drunk on the blood of the saints, and with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus,” Who are the saints, and who are the martyrs of Jesus?

In the final act of Babylon, Seizaki Zen faces down Alexander Wood on a rooftop. Wood has been seduced by the Whore into the irresistible temptation to commit suicide, which would have been a message to the whole world that suicide is a normal, acceptable act. Thus, the act Wood would commit is a great sin that will further accelerate the downfall of humanity orchestrated by the Antichrist Itsuki and his Whore. Seizaki chooses to invalidate this sin by shooting Wood, thus committing the sinful act and in a sense “absorbing” the sin of Wood, and obviating the resultant sin of humanity.

Seizaki takes upon himself the sin of humanity. That is the most I can really get out of this metaphor.

Throughout Babylon, the major plot point of the suicide law and its morality is constantly presented as a core fixture of the questions that are being asked of the viewer. Never mind that in much of the civilized world, around which Babylon revolves, suicide is considered de jure legal if conducted freely by a sole person; assisted suicide and euthanasia are still largely illegal. The object of the suicide law therefore is what it symbolizes; a new morality which embraces the radical freedom to choose to die, without it being seen as a bad thing. The truth is that much of society still holds negative opinions on suicide. If we suspend our normative notions of what suicide entails, the vast quantity of suicide prevention organizations and the efforts mobilized in support of this goal is somewhat astounding.

There are many ways in which suicide prevention organizations advocate that may help a caretaker convince a suicidal person against suicide. Each of them offers a different perspective of why people commit suicide, which may apply to different people in different circumstances. In one perspective, people commit suicide simply because their suffering in the moment is far too great for them to bear, and they are led to the desire to end the suffering in the moment. Thus, the optimal approach would be to ask them to give it more time and think about it. This is exactly what Alexander Wood does when speaking to the woman on the building – since you will be dead anyway once you make the decision, why not give it some more time to make sure it’s the correct decision?

Thus, in this presumption as with any, it is assumed that suicide is committed purely by emotional inclination. Indeed, Babylon’s string of Magase-induced suicides lend credence to that; Seizaki’s close associates who are able to speak with him before committing the act seem to invariably obtain some sense of orgasmic pleasure out of the act of suicide itself. The seduction of Magase, death, and sin overcomes the logical calculation of these characters, and they are unable to control themselves. It is precisely because of this framing of suicide as arising nearly strictly by emotional inclination that Babylon drives the audience towards the instinctive feeling that allowing people the freedom of committing suicide is bad.

That is precisely the distinction Babylon uses to convince the viewer that suicide is bad. Whenever one talks abstractly about suicide, it is always talked about in a rational manner. Itsuki Kaika declares his desire to sacrifice his life to save his son. Alexander Wood speaks about the ethics of suicide, and ponders its objective morality in relation to the Bible. The French President opposes permitting suicide in consideration of the socioeconomic outcome that would result from granting citizens this freedom. Yet, every individual we see commit suicide does so purely out of emotion. The vast majority of death is driven by the strangely sexualised compulsion to kill oneself that is implanted by Magase Ai. This is the essential jarring difference in Babylon which makes the two parallel stories conflict with each other, unless you accept the normative presupposition that suicide is both (i) emotionally-driven, and (ii) bad. The disjoint between how suicide is spoken of by the proponents of it and how it is actually carried out therefore leads the viewer into the understanding that the proponents must be deceitful. How could they talk of such high-minded ideals with no real understanding of what really happens on the ground? They must be either ignorant, or attempting to manipulate us into doing what they say. This presupposition is what lies behind the eventual moral conclusion at which the show arrives, through Wood: good is continuing, and evil is halting.

What does that line even mean? If you take a cursory glance at the r/anime thread on the last episode, nobody can really tell you. I can’t tell you. My closest guess is that Wood has accepted a fundamentally biological principle of life, wherein good is derived from the perpetuation of life, this being the indisputable goal of pretty much all life itself. Thus, taking actions to stop life before it has reached its natural course is to be considered evil. This is also used to explain why we celebrate births and mourn deaths. It is, of course, a very simple moral stance, and not an altogether uncommon one. It just doesn’t necessarily always hold up to the moral dilemmas that were already put into the show before this moral principle was introduced, and that would be typically used to question the moral principle to begin with.

The conspiratorial attitude which the show imparts to the viewers gives Babylon a visibly political bent. It parallels the conspiratorial attitude with which much of society views the more extreme progressives today. Why would the politicians thump their chest and declare our country open to migrants and refugees if not to manipulate us into the great replacement of our esteemed race? Why would our government seek to make transition easier for children with gender dysphoria if not for the oppression of women and eventual pedophilia? Why would there be a mass-shooting if not because Obama wants to use it as an excuse to take away our guns? While the story of Babylon can comfortably accommodate this conspiratorial thinking because of the genre in which it (uncomfortably) sits, the truth is that the right to suicide is a sensitive, real-world issue and in many ways the conspiratorial thinking which Babylon implants in viewers can and will carry over to one’s real-world outlook.

Through the allusions to Biblical morality that are evident in the nomenclature scattered throughout the show, and even in the show’s name itself, Babylon makes its stance on the morality of suicide pretty abundantly clear. Man is seduced to suicide by a slick-talking politician who speaks of rights and progress but in actuality is an Antichrist-esque figure who works with the Whore of Babylon to orchestrate our downfall. We are constantly questioned on questions of good and evil by both Magase and Seizaki, but with the instinctive understanding that Seizaki is good and Magase is evil. Seizaki proclaims that the meaning of justice is the continual consideration of what is good and what is just, a profound-sounding aphorism that does not hold up to scrutiny. He questions good and evil, but with a strictly moral overtone and at the same time largely conforming to social, legal, and moral norms. Functionally speaking, he barely questions the good and evil of what he is doing, since beyond that proclamation he isn’t observed to question more than procedural norms of justice in the show. Magase questions good and evil with no obvious conclusions, but with actions that push the boundaries of these norms and a distinctly amoral tendency. It’s hard to consider her in any way good when she dismembers the main character’s closest ally on screen, all the while shrieking nonsense about what is good and what is bad.

All this is well and good for a mystery thriller story. In fact, Babylon would excel as a mystery thriller, with the stakes of failure being the very soul of humanity itself. The religious references, magical realism, and constant catch-up game being played by the good guys rubs my chuunibyou soul in all the right places. What it is not is a proper critique on the human condition and our relationship with death, which it teases us with. All the chips were properly set up in the first arc – questioning whether the relationship should be one of fear, willful indifference, or blissful eventuality, but they were just left there while the story took its own different track. In so doing, the show not only fakes out on its attempt to question, it doubles down on the internalized sense of dread we feel when contemplating our own deaths. It would have been a good show, had it been more open in allowing the audience to truly contemplate death on their own terms rather than tying it all into seduction and Biblical prophecy. It would have been a good show, had it properly humanized its villains in a way that didn’t seem like a grand manipulation and deception by the Devil and his Whore. It would have been a better show, had the writers been able to grapple with this theme in a truly introspective fashion before creating the show.

It didn’t, it wouldn’t, and they couldn’t. This show is a lie. There are so many other problems with the show that can be raised; the innate Madonna-Whore Complex in the representation of the main characters, where the female is either the extremely competent and righteous parallel to Seizaki or a Whore who has had this supernatural shape-shifting sexual seduction since she was in the throes of puberty. The framing of characters in order to make them obviously morally upright, corrupt, or amoral without further need for consideration. The inclusion of elements and characters that are never mentioned again in future episodes, and turn out to be a red herring. That goddamn paper printed with F all over, where Seizaki stares at it in foreboding and says “F… for… FEMALE…” The implausibility of a mayoral candidate bringing up a witness to a debate without clarifying the identity of the witness (who is a kid, and definitely needs parental permission to participate). The way it handles the moral questioning of the audience – literally Magase yelling a series of indeterminate questions at Seizaki. It’s a hot mess.

In a sense, it truly parallels the Bible in that it is hard to read (for the King James Version I was brought up with), dense to the reader without intense contextual scrutiny, and unrewarding once you figure out what is truly going on in the text. I assume this is the goal it meant to achieve, and if so, it did it grandly.