So I’ve been planning a big banger of a trip to Japan for a really, really long time. The last time I was there was in 2016, and I quite honestly feel like I wasted my time there because I had no idea what I wanted to do. I still have quite a few zany stories from that trip, in particular the experience of watching the right-wingers in their cute little truck driving all over Tokyo declaring that the Emperor was still the rightful sovereign who was being held down by American tricksters that were still actively waging a war of shadows on the subjugated Japanese people, or their cute little parade at the Yasukuni Shrine at the end of their long day of hard work spreading strange propaganda.

With that in mind, trying to figure out exactly what I wanted to do there was a key consideration. As a grade-S weeaboo, I have a lot more affection for Japan than for most of the places I have been to in the past five years – Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, Hong Kong, Macau. Flight tickets to Japan are also pretty expensive given the sheer popularity of the destination; it already is a hotspot during normal times (whatever the hell that means), but the cheaper yen and post-pandemic “revenge tourism” are really ramping up the numbers of tourists who want to go there, to the extent that it’s causing actual social issues at the moment.

Given the amount of money I am spending on this trip, people wondered what I would want to do there. I myself feel sort of pressured to provide some account for why I choose to do particular things versus others amongst the range of things that exist there, to justify the choices that I make. In Singapore, among my friends that travel often, I hear of various reasons. I’m not someone who will say that all reasons are “valid”; I think some reasons are more frivolous than others. You can think of Mill’s framework of higher versus lower pleasures, which argues that pleasure can be segregated by quality. Not everyone has this intuition regarding pleasures; some may argue that the quantity of pleasure alone is king. If one finds the pleasure of eating a good meal greater than the pleasure of reading a good book, then one should milk the former pleasure for all it is worth.

Pleasure elitists like me (I hope to be called this someday) would argue that the value of pleasure cannot simply be situated in the raw pleasure of the act alone; Mill calls on the concept of dignity, but I think that’s a particular way in which a pleasure can be construed as higher. For the purposes of regular conversation with people not really into analytic philosophy, this intuition functions more like a smell check, a gut feeling. I’m sure you’ve heard of a thing that your friend did on a holiday, and wondered: wow, was that really worth it to spend your valuable time on an overseas trip doing that? Wouldn’t it have been better to do [insert other thing that you think is more worthy]?

In either case, it is because my brain works like this that I find myself having to defend the value of my choice to blow nearly JPY100,000 on an anime character’s birthday event during a leg of a trip entirely dedicated to the series it comes from.

Aside from that, I also do wonder if I have over-hyped this leg of the trip for myself. There’s this apocryphal thing called the Paris Effect, mainly associated with Japanese people, wherein people have hyped up Paris so much in their heads that when they finally get to Paris they have mental breakdowns over the fact that Paris very much cannot live up to their expectations even if it was trying to. France is often treated in media as a foremost global epicenter of culture, romance and refinement; most of the things we associate with haute couture (itself a French word) inevitably find themselves connected with France. So when one gets garbage hurled at them on le metro parisien by a random racist drunk man calling your family names before splashing the window by their seat with the leftover beer in their can on the first day there, as I have, it can come as a bit of a rude shock.

Some part of me is worried that this will happen with one particular leg of my trip. I hope you will enjoy my explanation of where I’m going, why I’m going there, and why I’m worried, and parse some thoughts you have about your own travels in our media-driven age.

In the beginning, there was nothing. And lesbian writer Kimino Sakurako, who has had altogether too much influence on my life starting with Strawberry Panic!, said “Let there be Love Live!”

Thus, the initial generation of the Love Live! School Idol Project was revealed in Dengeki G’s Magazine, announcing a collaborative anime project between ASCII Media Works, anime studio Sunrise and music label Lantis. Bushiroad would later be added in as publishers of the game Love Live! School Idol Festival (SIF) that was developed in KLab. KLab was not involved for the sequel game SIF2, which is probably why the game’s release and end of service were announced in the same tweet.

The basic concept of the series, as you could probably guess, is high school girls being idols. This isn’t that surprising on its own – idols tend to start young to begin with, and youth is an incredibly prized commodity in the idol industry. It is very, very rare to see even top idols continue into their mid-twenties; smart ones will use their short burst of fame as launching pads into other parts of the entertainment industry, or end up languishing in adult entertainment or other less-than-savory services. There’s a lot of good research into why the idol industry, whether in Japan or in Korea, is generally not great1. As a way to circumvent that in some sense, I got myself into 2.5D idols where there remains some thin layer of separation between the character which fans can parasocially attach themselves to and the voice actresses. Feel free to tell me if my read of the situation is cope.

The real innovation of Love Live! is that these idols are amateurs in canon. Its main competitor is the iDOLM@STER franchise, which is owned and managed by Bandai Namco. This lends itself to a sort of DIY aesthetic. In the universe of iDOLM@STER, the player/viewer is typically positioned as a professional idol Producer, with commercial and business support. The songs are written for the idols that you produce; they take lessons with professional coaches; much of the focus in iDOLM@STER is on the actual day-to-day work of being an idol; and so on. In Love Live!, the audience takes for granted that the girls do do everything themselves – composition, choreography, costuming, filming, editing, marketing, sponsorships, and so on – on the side of what we actually see them do. It also merges the core real-world promotional activities of idols – performances, music, fan meets – with the illusion that the school idols are essentially simply carrying out club activities.

At the time of writing, Love Live! has been active for a little over the past decade, and currently consists of 5, maybe 6 generations depending on how you count them. Aqours is the second of these, and its attached anime product is Love Live! Sunshine!!, and it is this group that is my focal point right now.

Aqours’ story is deeply linked to the legacy of the first group, μ’s, whose core driving force in the original run was to become popular through the then-relatively-obscure Love Live! competition in order to attract new entrants to their beloved school, Otonokizaka Academy. Over the course of a year, they manage to succeed in saving their schools, and creating history by being the most famous winners of Love Live!. Faced with the graduation of their third-year members, its leader Kousaka Honoka decides to disband the group.

Aqours exists about in a post-μ’s world, shaped primarily by the actions, legacy and shadow of μ’s. The show actually does quite a good job of leading the audience by the nose for the first season, making you think that Aqours is really little more than a rural reboot of μ’s destined to succeed in the same way they did. Both groups have nine girls, with each of the three years of high school represented by three girls. Both have a fearless leader with orange hair. Where μ’s wants to rescue Otonokizaka, Aqours wants to save Uranohoshi Girls’ High School.

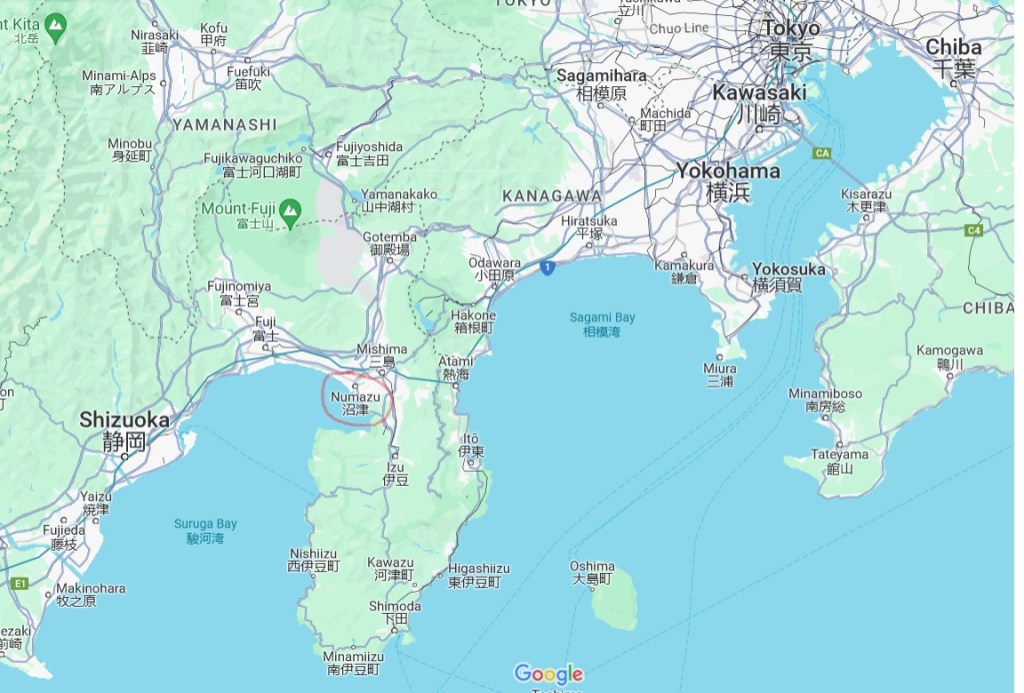

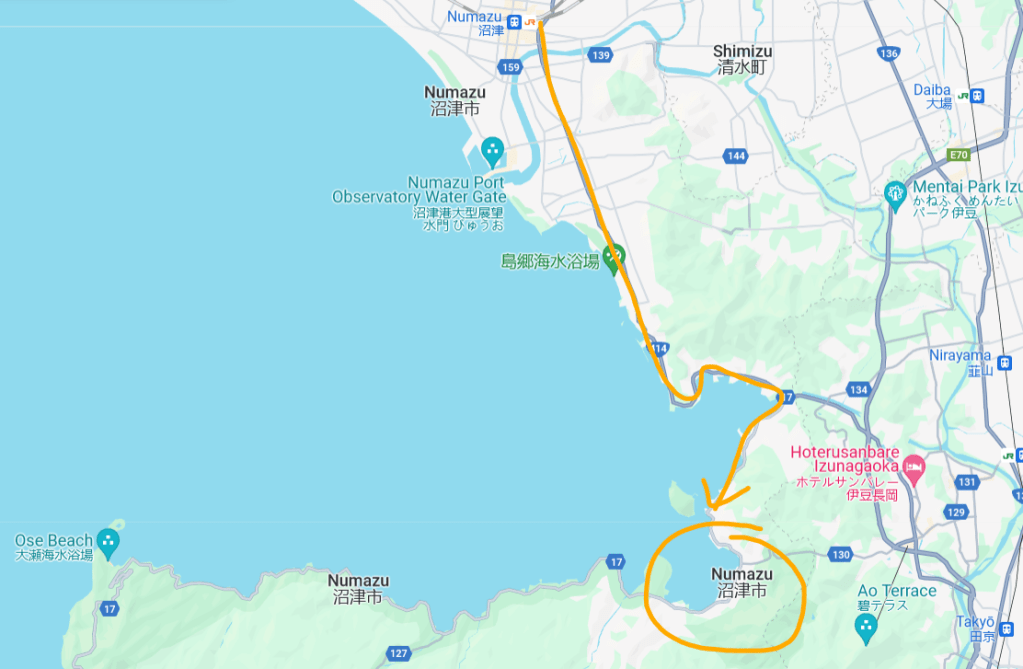

The original series was, however, set in Tokyo; Sunshine!! is set in the town of Numazu, which is… sort of in the middle of nowhere. It’s not really in the middle of nowhere – if you look properly, it’s actually situated nestled in a beautiful area between Mt. Fuji and the ocean, conveniently accessible by train – but it’s not really been relevant to much of anything for a long time. Numazu sits at the entry point to the Izu Peninsula, and just south of the city is the town of Uchiura (highlighted in orange), where the vast majority of the show takes place.

The first season is not only about the group getting together, but it is also about getting over this failure. From the first invitational performance they give in Tokyo where they receive zero votes from the audience to the prospect that they are unlikely to actually be able to save their school, they have to figure out a reason for continuing their activities as Aqours. Ultimately, the country girls cannot feasibly succeed. Nobody will go to a remote school on a hill in a sleepy fishing village, just because some of its students are famous idols right now. From there, the second season shows the bonds of the group being forged ever closer, and lead ultimately to their victory at the competition on their own terms – nevertheless, their school closes and they are forced to merge with a different school. I hope you’re happy that I have been this concise in explaining the plot of the show without having you sit through very much of it.

If you’re not already in idol hell – the term fans of series like Love Live!, BanG Dream!, iDOLM@STER and other similar franchises use affectionately for our affliction – I’m not sure there’s little I could do to get you emotionally invested in the entirety of the show barring literally sitting you down and watching it with you. That’s sort of linked to what I want to discuss, but not entirely. The important point for now is that the way in which the show uses the town as more than a set; it exists symbiotically with the location in real life. Let me bring you into the diverse ways that a real-life town can connect itself to fictional characters.

In the original series, μ’s is linked to the area of Akihabara because of its pre-existing significance as a pop culture site. However, this means that Akihabara truly exists mostly as a set; it is where things happen. You can move the story of μ’s to any other metropolitan area and the contours of it would not change that much. The story of Aqours is, on the other hand, deeply embedded with the location to which it is tied to the extent that any serious viewer cannot but develop the same romance for the place that the characters have. Instead, Numazu feels like “home”, with many of the plot points of the show revolving around the different specialties of Numazu and the attachment of the characters to it.

The show drips with local flavor, and I want to show just a few really obvious examples of how the show absolutely drills deep and mines Numazu for it. Key scenes of the show are set against real-life locations that you can find, and you can walk around. Episode 2.2 is set in a temple, when the girls come together to take shelter while ironing out their musical differences to write a song.

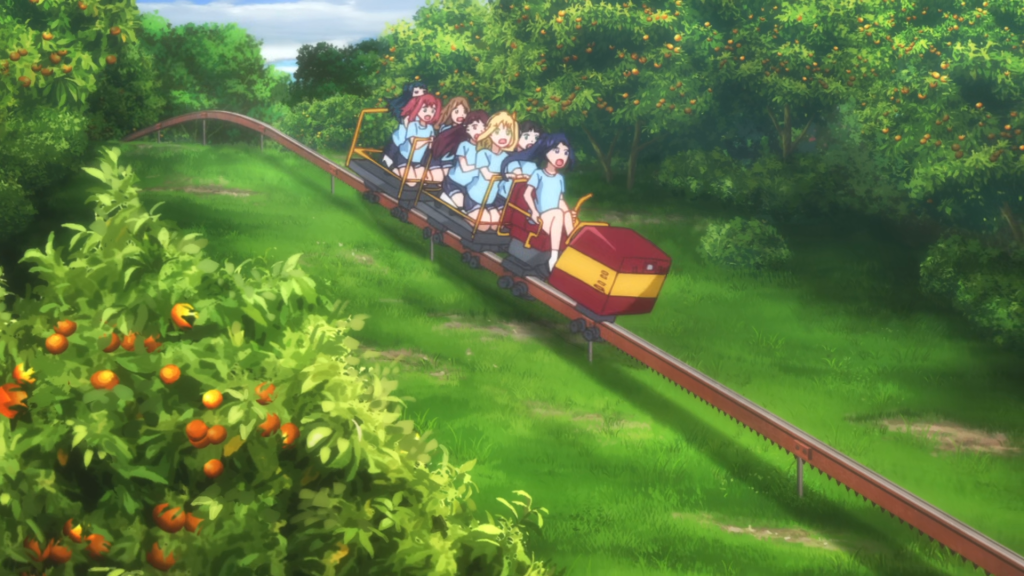

Episode 2.3 is set in the orange fields, when the girls take advantage of the local infrastructure to make it from performing in the qualifiers back to their school in time for the school festival.

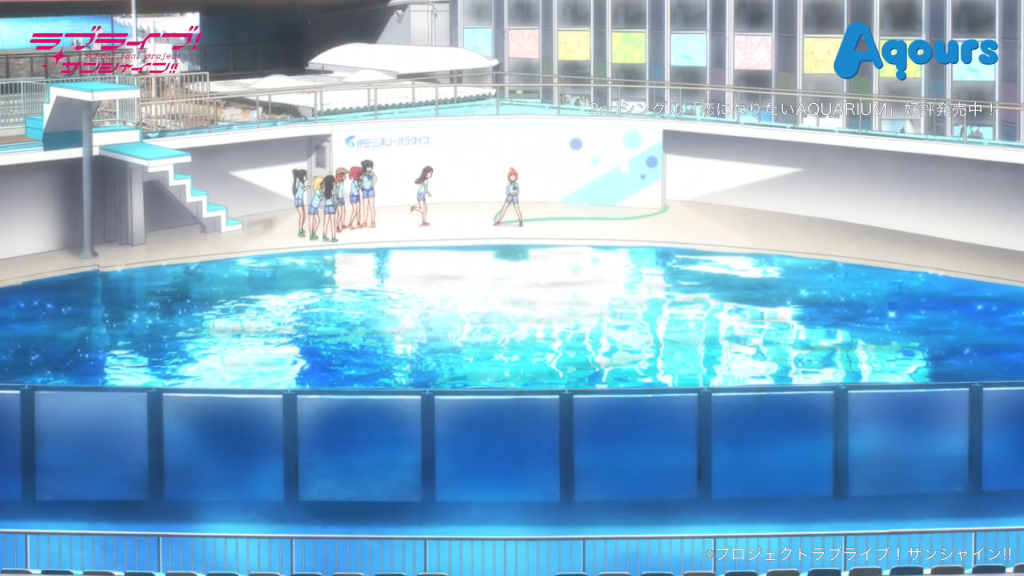

Episode 2.4 is set in the Izu-Mito Sea Paradise.

Its walrus mascot, Uchicchi, is commonly associated with You because of this episode where she wears it.

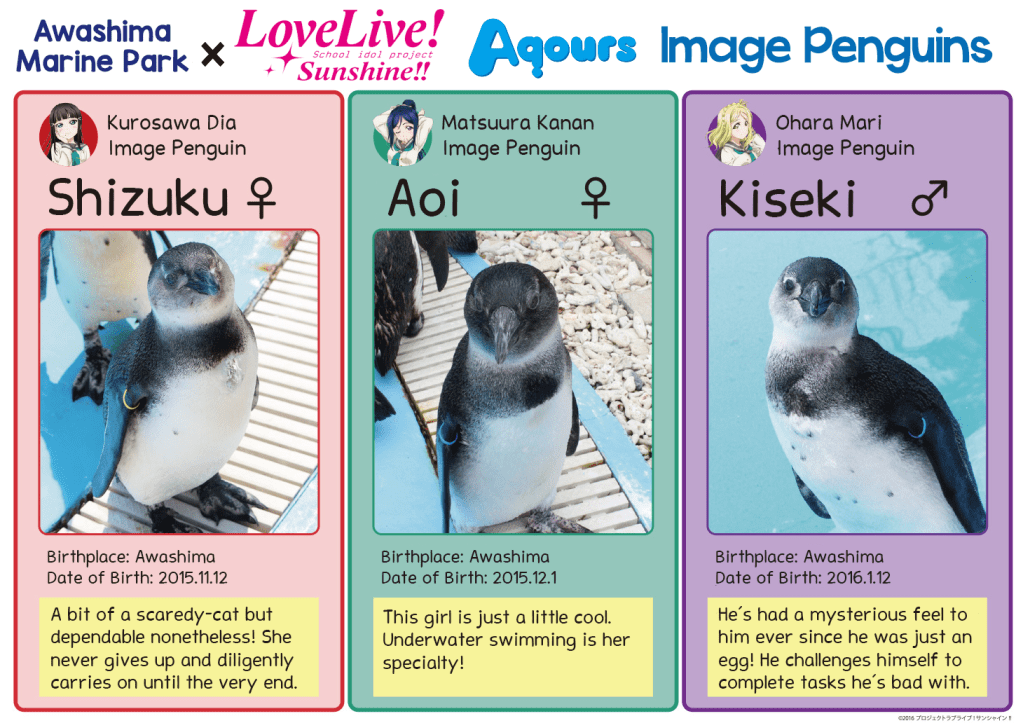

Penguins are also a staple of the show, and Awashima Marine Park actually has 9 penguins themed after the characters of Aqours as well.

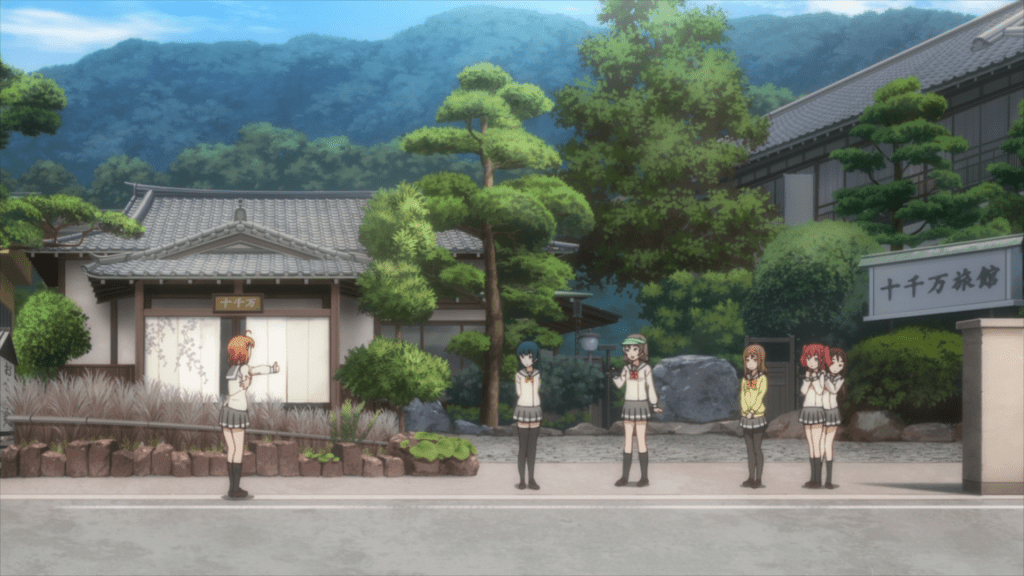

This also includes the canon homes of the Aqours girls, much of the investigation for which comes courtesy of MikeHattsu Anime Journeys. Takami Chika, the leader of the group and my favorite one, canonically lives in Yasudaya Inn. Naturally, a stay in Yasudaya is non-negotiable for this trip and for all future trips.

Sakurauchi Riko lives in the house across the road from Chika’s, although the distance is much shorter in the anime than in real life.

Watanabe You’s house is located on where the Orandakan cafe sits, but is not the same building.

Ohara Mari’s house is located on Awashima Hotel on Awashima Island, together with the Awashima Marine Park.

Matsuura Kanan, the third-year, is a diver and also lives on Awashima Island in a small diving hut that in real life is a frog zoo beside Awashima Marine Park.

Kurosawa Dia and Kurosawa Ruby live in the house of the old, quasi-aristocratic Ookawa fishing family in the region.

Tsushima Yoshiko lives in an apartment complex deep in urban Numazu, called Natty.

Last, but not least, Kunikida Hanamaru is a shrine girl, and her home is based (I think!) on the Joudoushuu (Pure Land Buddhism) Raikou Temple, somewhere in the suburban sprawl behind Yasudaya. It’s also the one that they took shelter in in episode 2.2. Mike hasn’t recorded this one in his blog yet, but I’ll see if I can compare it in real life when I’m there.

Even more recently, 2023 saw the publication of an Aqours-themed travelogue with unique character art laid over iconic views in the town, titled “Find Our Numazu – Landscape with Aqours”.

The setting of Numazu was further reinforced by the 2023 spin-off series Yohane the Parhelion: Sunshine in the Mirror. Tsushima Yoshiko, who will insist you call her Yohane, is beloved by fans for her delusions of grandeur and “fallen angel” persona; playing off of the isekai craze in anime, a fake trailer was released on April Fools’ Day in 2022 recasting the show in a low fantasy Numazu with Yoshiko as the protagonist. It was eventually confirmed that the show was actually being produced, and the final product focused even more on Numazu as a place. Yoshiko’s arc follows her failure to make it big in the city (Tokyo) and returning to her hometown. Initially isolated from the community, she cares little for the location itself, but by reuniting with her old best friend that she abandoned and meeting new people all over town (the original cast of Aqours recast into different roles), she develops a sense of Numazu as a place: home.

Unfortunately, because of the fantasy nature of the setting, Parhelion is ironically less embedded into the actual scenery of Numazu as a place than the original Sunshine!; it is a place in concept, but few actual sites are explicitly tied back to real-life locations as heavily as the original was, which was a curious choice to me. Instead, as a derivative spin-off work, it taps into the pre-existing nostalgia that has already been fabricated for Numazu within the fanbase, which is why I generally don’t have very much to say about Parhelion. I wish they’d included more real-life locations within Numazu rather than just generally pointing back at Numazu.

Very recently – I’m talking like the same month as I’m writing this – cult hit camping anime Yuru Camp is having a spinoff with Sunshine!!, focusing on camping sites and cultural destinations across broader Shizuoka.

Thinking in advance about why I want to visit Numazu – a process that has been distilled by confused friends trying to figure out exactly why I’m doing this – the best answer I can arrive at is that I want to be there because Aqours “is there”. The part of this journey that I think I most enjoy is looking at a beloved place through beloved characters’ eyes. We inscribe meaning onto a variety of things, and the sharing of these things is an intimately revealing act. Terms of endearment that can no longer be used because they have mentally been reserved; outfits purchased as part of a matching pair but now missing its companion; abandoned playlists whose songs you once knew by heart. Places are one of the most easily shared intimate things, given that they tend to change rather slowly and are typically something you can choose to engage with or not – you get to decide whether your feet will bring you to a place or not.

My real goal, then, is finding the sense of closeness with the characters who fought to preserve a place that they hold dear. It isn’t simply to interact with the other fans of Sunshine!!, though I expect that will be fun in its own right. It isn’t to buy merchandise related to the franchise, although it is a secondary objective and I’m sure the merchandise I do buy will be imbued with a great deal of meaning for me. It isn’t to participate in events related to the franchise, although I will be spending quite a pretty penny at Ohara Mari’s birthday party and at Takami Chika’s canonical ryokan home. Our home is home because of the people who are there, and for the fans of Sunshine!! Numazu is home because Aqours is there.

But that sensibility in itself troubles me. This isn’t home, and I know this isn’t home. Why am I so attached to a place simply because it belongs to fictional people I will never get to meet, sold to me by a consortium of Japan’s largest media conglomerates?

The term “contents tourism” was first employed in the Survey on Regional Development through the Production and Use of Video Content2 by the Japanese government. This would form a basis for the Tourism Nation Promotion Basic Plan that was published in 2007. The key contribution here is that the survey and its findings helped Japanese authorities to recognize the commercial value of tying ideas to places and actively marketing them on that basis. This concept would be later picked up by Professor Philip Seaton, whose work is primarily within the realm of Japanese culture, both modern and historical. He is largely responsible for the broader pickup of content tourism as a phenomenon outside of Japan. Together with his colleagues, he formalized an academic definition of “contents tourism”3 as follows:

“… travel behavior motivated fully or partially by narratives, characters, locations, and other creative elements of popular culture forms, including film, television dramas, manga, anime, novels, and computer games. ”

This definition is actually so self-explanatory that my initial response to this was to hang up my pen and concede. I have, once again, been vindicated in my belief that many ideas I have had have already been expressed somewhere out there in the world, better than I ever could have. I won’t try to change this definition, or assert that I can expand upon it, but I do think I can connect it to some other threads. Essentially, the argument that Seaton tables is that contents tourism is the attachment of a particular form of mediatized meaning to a place. He differentiates this from heritage tourism, that is the visitation of a place because of reverence for its historical significance. Contents tourism is a product of the contemporary popular culture of the period itself, and overlaps with heritage tourism insofar as history is turned into content. More often than not, these are historical drama TV shows, which are very prominent in Japan via the Taiga drama.

Every year, the national broadcaster NHK pulls together a large-budget, high-profile historical production that runs through the entire year. Each episode, released weekly, is nearly an hour long, and in its modern form every series focuses on a particular individual. The production quality is incredibly high, and given the insanely high TV ratings that can reach upwards of 60% at the start of new seasons, successive seasons and the discourse around them reflect significantly how Japanese people view their own history. The funny part, however, is that each episode always ends off with a travelogue of key places in that episode, exhorting the viewer to visit them to physically connect with the history that they have just seen dramatized.

The travelogue you have just seen is from the 39th episode of Segodon, the Taiga drama series of 2018 that is based around the life of Saigō Takamori. It’s my favorite Taiga series so far, and that’s why I used it as an example, but it’s been a staple of Taiga since at least as far back as 2010’s Ryōmaden, centred around Saigō’s contemporary Sakamoto Ryōma. Studies before the incorporation of pilgrimage-style travelogues into Taiga demonstrated their value, and studies after have shown how contents tourism has blossomed after their implementation. Slowly, the set pieces of the Taiga drama would shift to more explicitly address the stage on which it stands, to tie the events more closely with the place in addition to the people involved in it and presenting the whole package to the Japanese viewer who would then be inspired to visit to connect to their own history. I haven’t watched enough Taiga to be sure, especially not old Taiga, but there is a 1990 series that featured Saigō, Tobu ga Gotoku (As if in Flight), that we can compare with.

Saigō had two recorded deeply intimate romantic relationships in his life; the first was when he was exiled to Amami Ōshima, an island under the control of his Satsuma clan that was being worked effectively as a sugar plantation economy akin to what one would find in the age of colonialism and imperialism. This wife, Aikana, was afforded one episode in Tobu ga Gotoku; in Segodon, she is afforded four episodes, and returns briefly in two or three future episodes.

Some of this can be chalked up to the differing focuses and scopes of the show, with the earlier production much more heavily focused on Saigō’s differences with childhood-friend-turned-despot Ōkubo Toshimichi and the ensuing Seinan War, and the latter exploring more deeply his formative younger experiences. Yet, I’m also sure that Amami Ōshima just made for some really banger travelogues and provided the NHK a chance to briefly revitalize a remote, easily forgotten corner of Japan with tourist attention. Returning to anime as a genre in particular, the percentage of anime which includes real places as settings increased from less than 5% of all anime released in 2000, to around 30% in 20154.

Thus, we have to distinguish between the phenomenon of contents tourism – subdivided into genres based on the form of the text with which audiences interact and that confers the meaning onto the place – and the corporate strategy. More commonly, it has been the case that works are created based in locations without aiming to promote tourism, but do so as a side effect. Think modern-day Eat, Pray, Love journeys or Around the World in Eighty Days journeys. Thus, some novels may focus on the authors’ experiences in particular cities, but never really focused on specific, real sites within the cities other than the ones which were already tourist attractions. In other words, most literary tourism links their work to a city or region, which the reader may get the desire to visit.

The reason why contents tourism is mainly explored in a Japanese context is that is uniquely intentional and explicit in promoting this brand of tourism. This is not to say that they were the first to do it; tourism fiction, or fiction created with the promotion of a tourist destination as a primary goal, has been around in a modern context for a while.

… I’ve never personally read any non-Japanese works, but a brief Wikipedia search tells me that Blind Fate by Patrick Brian Miller was the first modern tourism fiction novel with an integrated digital travel guide. I interestingly once read a Holy Land travelogue attached to the Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolimitanorum, or The Deeds of the Franks and Other Jerusalemites/Jerusalem-Bound Pilgrims, an anonymous primary source on the First Crusade5. Does that count?

If he who wants to visit Jerusalem from the western areas, let him always hold to the rising sun, and he will discover Jerusalem’s places of prayer, which are noted here.

In Jerusalem, there is a little room, which has a single stone for a roof, where Solomon wrote the Book of Wisdom. And there, between the temple and the altar, upon the marble before the sanctuary, the blood of Zechariah was spilled.

From there, not far away is a stone to which Jews come every year and which they anoint, lamenting, and then go away groaning.

There is the house of Hezekiah, the king of Judah, to whom God gave three times five years.

Next is the house of Caiaphas, and the column to which Christ was bound and struck with a whip.

At the Neapolitana Gate, is Pilate’s Pretorium, where Jesus was judged by the high priests.

And there, not far off, is Golgotha, that is, the place of the skull, where Christ the Son of God was crucified, and where the first Adam was buried, and where Abraham sacrificed to God.

From there, a great stone’s throw toward the west, is located the spot where Joseph of Arimathea buried the holy body of Lord Jesus Christ; and there is the splendid church built by King Constantine.

It just goes on for this for a while, and relatively speaking it’s unique for its era. You can really see the reason why content tourists often refer to their travels as pilgrimages – they bear marked similarity to how the old pilgrims would also travel. I suspect that many religious pilgrims would, upon seeing with their own eyes the buildings supposedly once touched by the presence of Jesus, feel something akin to the deep joy and catharsis I would feel from going to the “holy sites” of Sunshine!!.

My concerns with visiting Numazu are twofold, and they stem primarily from the fact that Love Live! is ultimately a franchise. Despite my affection for the franchise, large-scale media projects like Love Live! will always be rooted in the corporations which create and promote them. As with any other beautiful experience the exchange of money sullies it implicitly. It is nevertheless interesting to note that Japanese media conglomerates, uniquely, have managed to figure out how to package characters and locations together and sell the whole thing. The closest parallel I can think of would be tourists who visit New Zealand to go on pilgrimages for Lord of the Rings; the commercialization of the place’s content value came as a byproduct of the movies’ commercial success and public acclaim. The producers of Lord of the Rings did not explicitly set out to make random hills and rocks in New Zealand famous. The selection of Numazu, on the other hand, was no coincidence; it was selected by committee with the key consideration likely being marketability, and thereby profitability.

I love the characters and I love the people behind them, but they were made to be marketable and to commercially exploit a relatively untapped tourist area. In Akihabara, competition is fierce for space and partners with which to conduct promotions; target an “unused” rural township, however, and you can set the terms for your partnerships in that area.

Don’t get me wrong – I don’t think this significantly impacts how much I love the franchise. I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect people to always look for small, niche artists to support, and I strongly believe that there remains a great deal of artistic merit in Love Live! as a franchise, and Sunshine!! especially among the others. But I am going to a town and blowing a load of money primarily because of a media franchise that was promoted straight into my brains and my hand, and even though I never knew about Numazu prior to watching Sunshine!! I am intent on making sure much of the money I spend is going towards the local economy as well. I am afraid that I won’t feel the things I hope to feel, and one of the factors counting towards that is how nickel-and-dimed I feel the experience will be. I had the pleasure of recently viewing Jenny Nicholson’s “The Spectacular Failure of the Star Wars Hotel” in time, where she expresses a similar view in the section on the cost of fan experiences from 25:15-32:36.

Framing is everything; if you pay extra for every aspect of an experience across many steps of booking, you feel taken advantage of every time it happens. It makes your relationship with the company feel antagonistic, as if they’re trying to get away with doing as little for you as possible…

This reason is mostly selfish. I think I hold the view that the exchange of money sullies things far more seriously than most around me, and am afraid that the inevitable merchandising and promotion will “ruin my immersion,” for lack of a better turn of phrase. But I’m also worried about how the town itself has been changed because of Sunshine!!. We know reasonably certainly that the commercialization of historical towns tends to leave tourists feeling less satisfied, as the development of mass tourism-directed products and services inevitably end up diluting the “essence” of the place6. I don’t want that feeling of connection that I’m looking for to be spoiled by overzealous commercialization, and I think that’s fair.

On that topic, I am more concerned – albeit at an arm’s distance – about the impact of tourism on Numazu. Tourism has absolutely benefitted the town in many ways; in an interview with Vice President Mine Tomomi of the Agezuchi Numazu Shopping District, she notes not only that it has brought monetary value to the town, its businesses and its people, but also that other Japanese fans of the show often travel down to help out for town-related events7. In 2020, some graduate students estimated that immediately after Sunshine!! aired in 2016, Sunshine contributed to between over 300,000-380,000 new tourists in 2017, creating a net economic impact of JPY 5.08-6.14 billion (in 2017, USD 45-54.5 million). Crucially, only around 16% of the spend was calculated to directly be on merchandise; the rest of that money had ripple effects on the rest of the town, especially in services, food products and transport8.

It is important to note that the benefits going directly to the town were not a foregone conclusion, and themselves underwent a process of negotiation. Nakakita Shun, in the Numazu Chamber of Commerce, said in a 2019 interview that tourism early on was primarily routed directly to Uchiura via Numazu, and tourists tended to not stop over much in Numazu; hence, many local businesses did not fully benefit from the rejuvenation. They held further negotiations with Sunrise – the company responsible for the anime part of the Love Live! project – to try and feature the city centre itself in the show. As a compromise, Sunrise agreed to establish a stamp book project in 2017, where stores scattered throughout the city have Aqours-themed stamps that can be collected in order to encourage fans to visit local businesses make purchases there9[8]. The implicit threat was that if local shopkeepers did not see the rewards from branding their town with Love Live!, they could react with hostility to anime pilgrims and deter them from going, thus torpedoing the whole purpose of Sunshine!! being set in Numazu to begin with. It shouldn’t be that surprising that season 2 (2017) and the subsequent capstone movie (2019), as well as Parhelion, featured the shopping district and town centre much more.

Anecdotally, Love Live! tourism has kept important town amenities attraction online. In February, Awashima Marine Park announced that it had to shut down as it had run out of money; this led to an outpouring of love from the community as they moved to visit the Marine Park before its closure. In April, a new CEO – a comedian who was also a fan of Aqours – was appointed to lead it, and it is now scheduled to reopen in July. Perhaps, if not for Sunshine!!, the Marine Park may not have been able to reopen so quickly, or may even have gone under much earlier.

All of which is to say that the town certainly knows how to reap the deserved commercial benefits from branding itself with Love Live!, and there are adept municipal actors who know how to properly negotiate for consideration from the companies involved in Love Live!. No, what I’m talking about is the treatment of the town itself, apropos of its place in the Sunshine!! canon. With the mass entry of tourists into Japan given the falling Yen, there has been a lot of discourse on the proper way to be a tourist given clashes between tourists and locals – I think everyone’s already heard about and discussed to death the erection of a vision blocker at a Lawson’s in view of Mt Fuji because of tourists’ bad behavior10.

One line that struck me in particular was an exhortation for tourists to not treat Japan like a playground; it is a real place where real people live, and there should not be significant impositions on their social mores for visitors. So, how ought I to behave in a town that has made itself a playground for one of my favorite franchises?

Going back to the part about historical towns, it is certainly the case that over-tourism often ruins the charm of places, especially rural places where a significant amount of the charm comes from that rural-ness. I certainly think this way, but it feels different for fiction-related content tourists. Sunshine!!, especially, hinges on the local qualities of the town and is unlikely to dilute that which it seeks to promote – although Parhelion could have been a misstep in this direction. Rather, what I think the mass tourism packaging process for fictional works like Sunshine!! inevitably do is reify the town, elevating and entrenching particular characteristics as symbolic of the town. An easy example is the mandarin oranges, or mikan. Idols tend to be assigned colors to make it easy to support them at concerts by flashing those colors, and to prime the audience to think of the idol via just the color itself; Chika’s orange hair is further tied into Numazu by linking it to mikan, which is one of the regional products of Shizuoka.

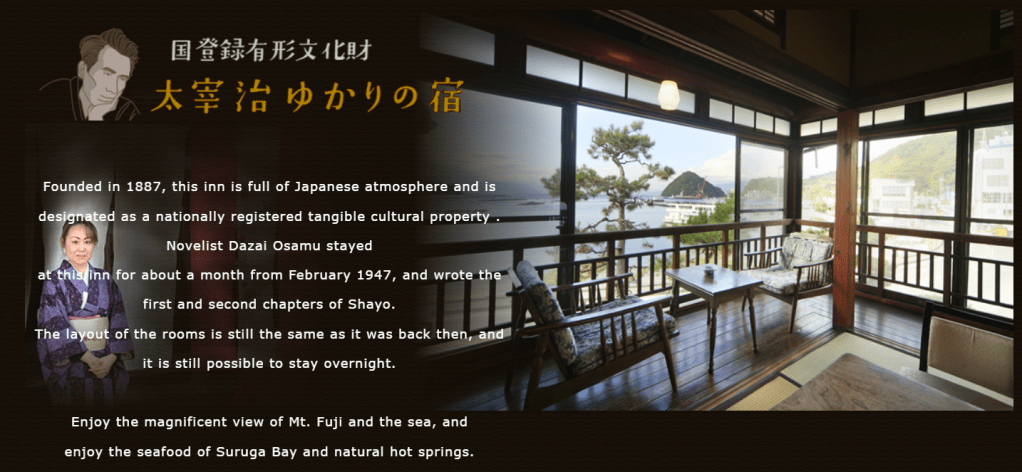

What Love Live! pilgrims associate Numazu and Shizuoka with, then, are largely dictated by what the franchise includes and elevates as essential aspects of the town, and this is more true for foreign tourists than domestic ones. When historical towns are typically commercialized with your average tourist traps, the danger is that tourists leave from the town losing its identity; for Sunshine!!, some part of me worries that Sunshine!! becomes its identity. The series will end, someday, and likely soon; our beloved voice actresses are, like me, pushing thirty. What next for Numazu? Part of me also wants to find out what there is in Numazu outside of Sunshine!!. As much as I love the series, it’s not timeless, and I don’t know yet how much long-term affection fans will keep for the town. I certainly will, or at least I believe I will. Perhaps someday Yasudaya Inn will cease to be Chika’s inn and revert to its previous, and generally more marketable, contents tourism link.

You have now gone the entire length of the piece without finding out until the very end that Yasudaya Inn primarily markets itself not as the home of Takami Chika, but rather as a former residence of the Meiji-era writer Osamu Dazai. They don’t mention Love Live! on their website… anywhere! They celebrate Dazai’s birthday, and mention everywhere they can that Dazai wrote the first and second chapters of The Setting Sun (1947) in one of their rooms, and it’s implied that Dazai found the inspiration to set his book in the Izu Peninsula – where Shizuoka and Numazu are located – while staying in the inn. The only reason I found out about this is because I wanted to book a room and read through the whole website beforehand.

Clearly, there are other things to know and love about Numazu that were never covered in the show, and will remain inaccessible to those who lack interest. I suppose the money spends the same for the business owners and the residents are now used to Love Live! fans shambling about their city, but I for one want to be a more thoughtful tourist.

I’m posting this the week before I embark on my trip to Japan – my thoughts really aren’t set in stone yet. It’s been a while since I properly travelled for leisure and had such great interest in what I will see – these are questions I will keep in my mind while going around the various sites. I will be documenting it and hopefully putting it up here. Iunno. I’ll see if I feel like it.

If you’ve made it this far and haven’t left yet, you have consented to being subjected to me fangirling. Here’s some homework extra stuff that I really like and want to share.

This music video is promotional material for the Aqours Club 2021 edition; Aqours Club is an annual subscription that gives access to special content involving the voice actresses. Every single shot of this video is filmed in the real-life equivalent of a location that’s significant in the anime, and related to the character played by the respective voice actresses. Pure kino.

SontokoroKobou (very very roughly translates to Hello Factory) makes bossa/acoustic arrangements of Love Live! songs, and I especially love this video for many reasons. Firstly, it’s one of my favorite songs in the franchise – it’s about thinking about how to apologize to a friend after an argument. Secondly, the visuals are really cute and also laid over an actual cafe in Numazu. Finally, the melody lends itself really well to bossa, and Sontokoro managed to sneak in a musical motif from a different song I like in there. Great!

This is an entirely fanmade music video of Takami Chika’s 3rd solo song, Namioto Refrain. This is more ballad-like, but her first two solo songs were much more in the style of traditional Broadway, motivated by voice actress Inami Anju’s personal affection for Broadway. Inami is now 28 years old, and slowly setting up her post-Aqours career, and also the first and only celebrity figure for whom I’m a paying fan club member. Go figure.

- Sakai, M. (2016). No. 31 When Idols Shone Brightly Development of Japan, the Idol Nation, and the Trajectory of Idols. Discuss Japan – Japan Foreign Policy Forum, 31. https://www.japanpolicyforum.jp/pdf/2016/no31/DJweb_31_soc_04.pdf ↩︎

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, & Agency for Cultural Affairs, Arts and Culture Division. (2004). 映像等コンテンツの制作・活用による地域振興のあり方に関する調査 [Survey] . https://www.mlit.go.jp/kokudokeikaku/souhatu/h16seika/12eizou/12eizou.htm ↩︎

- Seaton, P., Yamamura, T., Sugawa-Shimada, A., & Jang, K. (2017). Contents Tourism in Japan: Pilgrimages to “Sacred Sites” of Popular Culture . Cambria Press. ↩︎

- Suzuki, K., Sakaue, Y., Kunishima, M., Kuwabara, S., & Yasumoto Muneharu. (2020). アニメによる「聖地巡礼」を目的とした ファンと地域との関わり -沼津市を事例として-. Bulletin of the Faculty of Regional Development Studies, Otemon Gakuin University , 5 , 61–84. ↩︎

- Dass, Nirmal, ed. “Description of the Holy Places of Jerusalem.” In The Deeds of the Franks and Other Jerusalem-Bound Pilgrims: The Earliest Chronicle of the First Crusades , 109–11. United Kingdom: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011. ↩︎

- Lyu, J., Huang, Y., & Wang, L. (1177). When Essence is Lost: The Consequences of Commercialization in Historical Towns. Journal of Travel Research , 1–17. ↩︎

- Yamauchi, T. (2023, March 1). 『ラブライブ!サンシャイン!!』なぜ沼津の街に根付いた? キーパーソンに聞く、「地元」と「ファン」の蜜月関係と未来地図. Real Sound. https://realsound.jp/book/2023/03/post-1293472.html ↩︎

- Yu, J., & Onishi, K. (2020). アニメの「聖地巡礼」による沼津市の経済効果の分析. Japan (Nippon) Association for Information Systems Journal, 14(3), 8–12. ↩︎

- Kawashima, T. (2019, May 30). 「ラブライブ!」舞台の沼津 アニメ未登場でも「聖地」にしてしまう驚きの手法とは. ITMedia Business Online. https://www.itmedia.co.jp/business/articles/1905/31/news016.html ↩︎

- Reidy, G. (2024, May 8). Commentary: Mount Fuji overtourism furore tests limits of Japan’s hospitality. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/mount-fuji-lawson-view-block-overtourism-japan-yen-travel-4318181 ↩︎